History

Historical Notes about the Parish of Slateford Longstone

[Written by Stuart Harris, former Depute City Architect]

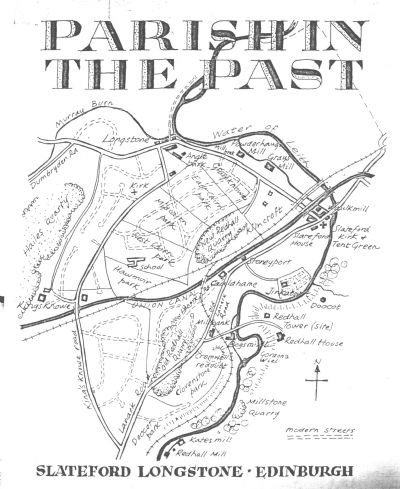

THE PARISH OF SLATEFORD LONGSTONE is part of the ancient parish of Hailes which King Duncan II, son of Malcolm Canmore gifted to the monks of Dunfermline Abbey in 1095. The first parish kirk, dedicated to St. Cuthbert, was somewhere near Hailes House, but later a new kirk was built in the crook of the river at Colinton. It was called Hailes Kirk until the 17th century, when the name ‘Collington’ (which exactly tallies with the local pronunciation of the name to this day) began to be attached to it.

The monks continued to be Superiors until the Reformation, but they feued out land in two estates- Easter and Wester Hailes. Easter Hailes, in which our parish lies, was feued by many notable men during the Middle Ages. Archibald Douglas, forefather of the famous Black Douglas of Bruce’s time, was laird at the end of the 12thcentury. In 1438 the laird was William Crichton, that crafty politician who arranged the ‘Black Dinner’ in the great hall of Edinburgh Castle, at which the young Earl of Douglas and his brother were brutally murdered.

In the seventeenth century the Brand family acquired not only Redhall Estate but parts of Easter Hailes across the river, and by 1712 most of our parish, except the tip of it beyond Kingsknowe Park and the land north of the Water of Leith, was joined to Redhall.

Originally, the Lanark road ran up the hill from Slateford, along what is now Redhall Bank Road and then across to pick up its present line just south of Kingsknowe [Dovecot] Park. At Millbank, the Bogsmill road branched off, forded the river and climbed steeply up to Redhall Tower. The Tower stood on the high promontory north of the present Redhall House, and dated from the 13th century. In 1756 George Inglis bought the estate, pulled down the old Tower and built the mansion house nearby, at a cost of £928:17:9. For another £40 he built the dovecote which you can see in Slateford Dell. It incorporates a heraldic panel brought from the old Tower, bearing the arms of Adam Otterburn, who inherited Redhall in 1533.

The Inglis family have owned most of the parish ever since, and George Inglis stamped their name upon the district when, in partnership with Joseph Reid, he started a bleaching and cloth -printing business at Inglis Green in 1773.

THE FARMS

The flats of Kingsknowe Court bear a name three centuries old. ‘Kingsknowe’ was nothing to do with royalty, but dates back to [a] man called William King who was farming this hilly part of the parish in 1656. Kingsknowe farm steading was demolished in 1964 to make way for the flats, and the Kingsknowe roadhouse stands on the site of the farmhouse [see additional notes].

Another farm was attached to Gray’s Mill (now McNab’s works). The field on which Longstone Primary School stands was called the Hawmuir Park, and between it and Redhall Crescent were three fields called the Cairn Parks. North of this, along the Inglis Green Road was the field of Graysknowe, and west of that (where Longstone Park now stands) was a triangular field called the Angle Park. East of Redhall Drive the Kilncroft fields stretched from Inglis Green to the south end of Redhall Park.

The third farm of the parish was Cauldhame. The farmhouse was beside the Lanark road where Redhall Bank Road branches off. Just north of it, on the canal bank, was Stoneyport, where you can still see the wharf which was used for loading stone from the quarries after the canal was opened in 1822. There were two of these quarries; the older one lies under the football pitches in Kingsknowe [Dovecot] Park, while the other one, opened in 1873, is now Redhall Park. The sloping field in the eastern part of Kingsknowe [Dovecot] Park was variously called Clovenstone Park (after a split standing-stone which once stood in it) or Roundel Park, after the knoll of trees which until recently towered at the head of Dovecot Grove, where Cromwell placed his guns one August day in 1650. An even older name for this field was Knockillbrae, which was probably Gaelic in origin.

WAR IN THE PARISH

It is not perhaps generally appreciated that in 1572-3 there was an exceedingly bitter civil war in Scotland, centred in the Edinburgh area. Mary Queen of Scots had fled to England and was imprisoned there. One party in Scotland - the ‘Queen’s Men’ - were for restoring her to the throne. The other party, headed by the Regent Morton, were for deposing Mary and making her baby son James, King. They were nicknamed the ‘King’s Men’.

Political and religious tension made the conflict very sharp indeed. The Queen’s Men held Edinburgh castle and many of the fortified tower houses in the Lothians. The King’s Men held the town of Edinburgh, Leith and many ither [sic] tower houses, such as Corstorphine, Merchiston, Slateford and Redhall. Most of the fighting was in skirmishes between parties scouring the countryside for food. There were raids on the tower houses - for example, Merchiston Tower was bombarded more than once. The war culminated in a siege of Edinburgh Castle- the longest in its history. Starved out, the Queen’s Men, commanded by Kirkaldy of Grange, eventually surrendered – only to have the terms of surrender brutally set aside after they marched out.

Redhall and Slateford were involved in these troubles. One day a group of farmers smuggling supplies to the Queen’s Men were intercepted at Slateford, and two of them were hanged and the others were branded on the cheek. The very next day five women were caught, but their sex didn’t [sic] save them: the King’s Men drowned one of them in the river and whipped and branded the other four.

CROMWELL AND REDHALL TOWER

Oliver Cromwell and his English army invaded Scotland in 1650. He came up the coast to Musselburgh, but found his way barred by the Scots army commanded by General Leslie. They were strongly entrenched behind a great earth rampart which they had formed between Calton and Leith – in later years it became the roadway of Leith Walk.

Cromwell decided to outflank Leslie by sweeping round the base of the Pentlands and cutting of his supply line to Stirling. He swung left to Fairmilehead; but when he got to Colinton on 16th August he found that Leslie had taken up a very strong position at Corstorphine, with an outpost in Redhall Tower. The route to the west was so boggy and difficult that Cromwell dare not leave his right flank exposed to counter-attack, and he was forced to stop and deal with Redhall, which was held by its laird and sixty men. Some of the English guns were hauled to the knoll at the head of Dovecot Grove, to fire across the river at the Tower. The bombardment started at dawn on 17th August and went on for six hours.

The Tower proved a difficult nut to crack. Not until its garrison ran out of ammunition was Cromwell able to attack with infantry, and even then the laird held out until sappers managed to get right to the Tower and blow up its entrance door. The laird surrendered and Cromwell was so impressed with his courage that he set him free ten days later.

On 27th August Cromwell marched westwards. Leslie attacked him at Gogar and Kirkliston. By this time the English were running short of supplies, and they were forced to fall back, first on Fairmilehead, and then on Dunbar. Leslie pursued them, but the Scots, spurred on by their exultant ministers, rashly exposed themselves to a counter-attack and were cut to pieces on 3rd September.

PRINCE CHARLIE IN SLATEFORD

On Monday 16th September, 1745, Bonnie Prince Charlie and his Highland army marched from the north into Corstorphine. Ahead of them they could see Edinburgh castle, bristling with guns and held for King George. The prince [sic] decided to by-pass the Castle to the south, and to try to negotiate a peaceful entry into the city. Thus he came by Carrickknowe to Inglis Green, where he commandeered Gray’s Mill as his headquarters, while his army bivouacked in the fields beside the road.

David Wright, the farmer of Gray’s Mill and Cauldhame, was understandably dismayed to see his crop of pease [sic] trampled by the Highlanders, and he was bold enough to go to the Prince to demand compensation. Charles offered him a promissory note, to be payable when the Jacobites were victorious; but the canny David looked doubtful and said he would prefer to have a note from someone he knew. Charles grinned, and asked if he would accept a cheque from the Duke of Perth – “who is a more credit-worthy man than I can pretend to be,” added the Prince wryly. With obvious relief, the farmer jumped at the offer.

Meanwhile the Prince had summoned the magistrates of Edinburgh to negotiate with him. That evening they sent out two successive deputations, each of which prudently came and went by the Netherbow Gate at the head of the Canongate, well away from the Castle guns. The second deputation left Slateford at three in the morning still asking for time to consider opening the city [sic] to the Jacobites. But a party of Highlanders trailed them back to town, and when the Netherbow was opened to let the coach in they rushed the city [sic] guard and captured the gate. Charles Edward had had only two hours’ sleep, still in his clothes, when word of their success came back to him, and he left at once to make a triumphal entry into the city [sic], which was rather spoiled by some cannonballs fired from the Castle. [see note below]

HISTORIC INDUSTRIES

Thanks to the sandstone which underlies it, and the waterpower of its river, the parish has an industrial history going back to the Middle Ages.

The earliest quarrying was for mill-stones for use in the local watermills. One was at Knockillbrae, in or near Kingsknowe [Dovecot] Park. The first of the great quarries for building stone was opened in the 17th century. It produced Redhall stone until the end of the 19th century, and was filled in to form Kingsknowe [Dovecot] Park. Hailes Quarry started to be worked around 1750 [see additional notes ] and the second Redhall Quarry (now Redhall Park) followed in 1873.

This was a major industry, supplying millions of tons of stone for the building of Edinburgh. Redhall stone was reckoned inferior only to that of Craigleith. Many feu charters in the New Town - eg. Those for Charlotte Square – required Craigleith to be used for the fronts of the houses, but said that the backs could be in Redhall. Hailes produced a strong stone in long horizontal beds, very good for making steps and stair landings, and in 1825 its output ran at the rate of 600 cartloads a day. In 1902 a brickworks was set up in association with Hailes quarry, but the brick was a poor one, and production died away in the 1930s.

The village of Longstone was the home of the quarrymen. Old residents say that it got its name from a huge block of stone which used to lie near the mouth of the Murray Burn and it is certainly true that the local pronunciation of the name is ‘Long-stone’ with the accent on the second syllable, not ‘Longs-ton’ as the postwar incomers call it.

Old Sandy Main, the late elder and beadle, could recall seeing a hundred quarrymen sitting of an evening on a dyke beside the river in Longstone. And he used to tell how the wives vied with one another, each trying to turn out her man on the Monday morning with the brightest, blackest boots and leather apron.

Of the five watermills that used to work in the parish, the remains of four are still to be seen. The dam above Slateford bridge supplied water to the Waulk Mill of Redhall, south of the aqueduct; Gray’s Mill, now owned by MacNab’s; and the Powderhall or Powderhaugh Mill just west of Slateford Public Hall. The Waulk Mill was for finishing cloth, and a mill of this kind was working as far back as 1546. The bleaching and printing of cloth started at Inglis Green in 1773 and dyeing and laundry work still goes on there.

Further up the river there was a mill on ground now occupied by the Parks Department nursery [now Redhall Walled Garden; see LINKS]. A Thomas Lumsden owned it in 1506 and it was called after him for years. By 1680 it was known as Redhall New Mill, and then it got the odd name of Jinkabout Mill – a name which also crops up in West Lothian. It was demolished in 1756 by George Inglis, the new laird of Redhall, so that he might form a great walled garden to be viewed from the grounds of his mansion across the river.

The fifth of the mills was called Vernour’s Mill in the 16th century, but by 1631 it had become Bogsmill. Here in the 18th century the early bank-notes of the Bank of Scotland were made under elaborate security arrangements. The workers lived at the Mill, their food being provided by the Bank. Twice a week a barber earned 3 shillings a day by coming out from Edinburgh to shave them. The frames which made essential water-marks were brought out by directors of the Bank, who stood over the men while they worked, and took the frames back to Edinburgh each night. The house at Millbank was built in 1742 as the house of the manager of Bogsmill.

Here the river twists and turns, and when the main buildings of Bogsmill were demolished in 1960 the rubble was bulldozed into some of the deeper pools. One of these pools, above the Bogsmill weir and under a steep bluff, bear the interesting name of Gordon’s Wheel or wiel. ‘Wiel’ occurs as the name for a whirlpool is several rivers in Southern Scotland.

THE UNION CANAL AND RAILWAY

The idea of building a canal between Edinburgh and Falkirk was first mooted in 1793, but the necessary Act of Parliament was not passed until 1817. Work began in 1818, and the official opening was in 1823. The canal was 31½ miles long, and it cost £461, 760. It is 5 feet deep, 35 feet wide at the waterline, narrowing to 20 feet wide [at] the bottom, and it could [carry] boats up to 69 feet long. The first passenger service, by the boat “Flora MacIvor” running between Edinburgh and Ratho, started in 1822.

The main traffic on the canal was that of carrying coal, stone and lime into Edinburgh. On the return journey the barges brought out the ‘polis dung’ from the stables, byres and streets of the town – which accounts for the coins and other small articles which are often turned up by the plough in fields in the district.

The passenger fare to Glasgow by boat was 5 shillings (cabin) or 2/6 (steerage) at a time when the coach fare was £1 (inside) or 14 shillings (outside). You could have breakfast for 1/2. But the Canal had to compete with the railway after 1842, and only seven years later it lost the battle and was bought by the railway for £209,000. Commercial traffic continued until 1933, and the Union Canal was officially closed in 1965.

Telford, the famous engineer and designer of the Dean Bridge, thought the Slateford aqueduct “superior to perhaps any in the Kingdom”. It was designed by Hugh Baird, engineer to the Canal, on the model of some of Telford’s work at the Ellesmere Canal. It is 60 feet high and 600 feet long, with 8 arches, and the Canal channel is formed in iron.

THE PARISH KIRK

Until 1782 there was no rival to the parish kirk in Colinton. In that year, some people left Corstorphine parish kirk, being offended by the introduction of the paraphrases into public worship – until then, the Kirk of Scotland had stuck strictly to the Psalms. In the following Spring there was a row at Colinton kirk. The leading heritor or patron chose a new minister, Dr. Walker, against the wishes of some of the congregation. Walker had been minister of Moffat, but he was also a keen botanist and held the post of Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh University. He was somewhat eccentric, and was widely known as ‘the mad minister o’Moffat’! The disgruntled parishioners walked out and joined up with the earlier seceders from Corstorphine. Together they began to worship in a chapel of sorts at Sighthill and placed themselves under the Associate (Burgher) Synod, which had been formed after other secessions from the national Kirk in 1733.

Other seceders joined them – some from as far away as Bristo, Balerno and East Calder – and in 1785 they built a kirk and manse beside the river in Slateford. South of the kirk was a large grass plot which was used for the open-air preaching on Communion days. It was called the ‘Tent Green’, after the awning which was put up to shelter the portable pulpit for the preaching. Mr. John Dick who had served the congregation as a student, was ordained first minister in 1786.

The present congregation of Slateford Longstone is the direct descendant of this secession kirk. It took part in the series of Church unions in Scotland, becoming first United Presbyterian, then United Free; and finally in 1929 it became a parish kirk of the re-united Church of Scotland. It occupied its old building from 1785 until November 1955, when the congregation walked in procession along Inglis Green to new premises at Kingsknowe Road North in order to be nearer the people of the parish.

Until the 1930s, Slateford and Longstone had been distinct villages separated from Edinburgh by green fields and country roads. Much of the parish south of the Canal and parts of its northern section were built up by 1939. After the War, prefabs were erected east of Redhall Gardens and in a strip along the east side of Hailes quarry. In the early ‘50s the primary school and a housing scheme were built west of Redhall Gardens. In 1964 the prefab estates and part of the old village at Angle Park were cleared for new houses and flats.

CORRECTIONS AND ADDITIONS

In prehistoric times our parish was the lower part of Water of Leith valley before that river entered a wide shallow loch which stretched from Gorgie to Corstorphine. This valley was one of the main centres of Bronze-Age settlement in Edinburgh. Burials of Beaker and Food-vessel folks have been found at Craiglockhart House and Juniper Green; a splendid gold armlet was found when the railway bridge was being built at Allen Park; and the great standing stone or chambered tomb called the CLOVEN STONE stood on a hillock in the vicinity of Kingsknowe Public Park [Dovecot Park], opposite Scott’s garage, until it was destroyed by the quarrying around 1880, and was so prominent that in about the 10th century Gaelic speakers were calling the slope up to the Dovecot Park KNOCKILLBRAE, meaning ‘the brae of the tombstone hill’.

The river’s name comes from the Celtic folk living here in the Iron Age. They called it LEITH, which meant simply THE WATER. There was a fort on Wester Craiglockhart Hill; and the Gaelic place name DUMBRYDEN, meaning ‘the hill town of the British’, shows that there was a centre of the Celtic Gododdin folk here in the west of the parish when Gaelic became current in Lothian about the 10th century.

From the 7th to the 11th centuries the Gododdin country was under pressure from the Anglians of Northumberland, the Picts from the north, and the Scots from the west. The name HAILES is Anglian halhs, ‘land in the bend of the river’, and may date back to the earlier part of this period. So may the name COLINTON which contains a Norseman’s name – it is ‘Kolbeinn’s farm’ – but it may belong to the 12th century, for some of the Norman-Frenchmen invited by David I to settle in Scotland had names of Norse origin. CRAIGLOCKHART is 12th-century, being named for Simon Loccard, a Norman-French knight. REDHALL, named for the colour of its stone tower house, dates from before 1337. Its lands lay east of the river, opposite Hailes, and including Colinton and Swanston, stretching over to the Biggar road.

‘Stoneyport’ did not originate with the Canal for it is at least 400 years older than it. It is properly STANIPATH, the ‘steep stony path’ up the brae from SLATEFORD, which took its name from the ancient river crossing before the 16th century and is ‘the slatey rock ford’. The farm names date to the early 17th century. The ‘Dovecot’ street name derives from the doocot of Hailes House, which stood at the head of the Doocot Park field some 400 yards south of the parish. LONGSTONE first appears on the map in 1812 as the two words Long Stone – ie: as properly pronounced. The long stone which bridged the Murray burn was replaced less than 50 years ago, and it is still there, now lying on the north bank of the burn.

INGLIS GREEN was founded in 1773 when George Inglis of Redhall leased land to Joseph Reid for a bleaching green. Reid went bankrupt in 1778, but the printing and bleaching of cloth was carried on by Hugh McWhirter and his son. The business prospered – over 7000 pieces of cloth were printed annually. McWhirter’s grandson John, born at Inglis Green in 1839, became a celebrated painter.

In 1849 George McWhirter sold out to the brothers Alex and John McNab. Thirty years afterwards, Alex McNab died and the business was taken over by his sister Elizabeth and her husband Alexander Stevenson, draper in Edinburgh. It now included tweed making as well as bleaching, dyeing and family laundry. In 1889 Stevenson’s sons formed a private company A & J McNab Ltd, and this became a public company in 1947. The business continued until 1983, when it finally closed down 210 years after Reid had started it.

The village of the Long Stone did not develop until the late 19th century. Before this, the quarry workers were housed further west, in the vicinity of Longstone Crescent and at Drumbryden [sic] or in the village of Hailes which was just north of Kingsknowe steading on a road which ran on the line of the present edge of the Quarry Park down to the bus garage. It was the encroachment of the quarry which led to desertion of this village in favour of Longstone and replacement of the road by Kingsknowe Road North.

KINGSKNOWES farmhouse was beside its steading – now Kingsknowe Court. “Kingsknowe House”, now replaced by “The King’s Knowe” inn, was a private house of about 1900. PEATVILLE was named after its builder, Peat of Juniper Green; and ARNOTT GARDENS was likewise named for its builders.

[transcribed with minor editing by Steuart Campbell of Longstone Community Council in November 2003]

Additional notes on Hailes Quarry Park

At its height, the quarry employed 150 men and 100,000 tons of stone were taken out each year. many more people were employed to cart the stones either to the railway station or to the builders. Sometimes as many as 500 cartloads of stone would leave each day.

The quarry was abandoned in 1902 when it had reached a depth of 100 ft and became flooded with 300-400 million gallons of water. This water was pumped out into the Murrayburn in 1949 to make way for a landfill site, which was gradually filled until the 1970s. It is rumoured that an elephant from Edinburgh Zoo is buried there.

When the landfill site was full, it was grassed over and in 1981 made into a public park.

(from Hailes Quarry Park News,Summer 2009, Edinburgh & Lothian Greenspace Trust)

More on Gray's Mill (2012)

The 1911 census reveals that, in that year, Graysmill Farm buildings were used as a haggis-making factory. See the ARCHITECTURE page for a picture of what may be the old Graysmill Farmhouse.

Kingsknowe Roadhouse (2016)

Records show that the Roadhouse site was occupied by 'Kingsknowe Auxiliary Hospital' (Slateford) during the First World War. Consequently the farmhouse may have been demolished during that War.

There are recollections of life in Longstone on a website run by Robert Laird (see LINKS).

For more on Prince Charlie's stay in Longstone see: http://the-lothians.blogspot.com/2012/04/bonnie-prince-charlie-slept-here.html